The Grapevine

AN INTERVIEW WITH:

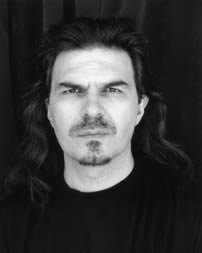

Nikos Dionysios

Nikos Dionysios trained at Art Theatre, Athens. As a writer and director he explores the universal symbolism in theatre from the Classics to the contemporary and also creates original works based on modern themes and poetry. His production entitled Ephemera was awarded Best Performance of  the Year in Greece. He has also presented work in North America such as: Ephemera: A Modern Trilogy with contemporary poets including Margaret Atwood; Bolero, a play about Isadora Duncan; Bread of Words. His one-man play, Rite of Passage was presented in January 1997 in Hong Kong and, more recently, at the Bridewell Theatre in London.

the Year in Greece. He has also presented work in North America such as: Ephemera: A Modern Trilogy with contemporary poets including Margaret Atwood; Bolero, a play about Isadora Duncan; Bread of Words. His one-man play, Rite of Passage was presented in January 1997 in Hong Kong and, more recently, at the Bridewell Theatre in London.

As an actor, Dionysios has twice been awarded Best Protagonists at the Festival of Athens for his performance of Orestes, and Eteocles in Seven against Thebes.

He has just returned from Paris having directed a presentation reading of the play La Reine D’Arles, prior to its premiere there in the Autumn.

He is also due to present Aeon and the Skeleton with music by Xenakis conducted by Roger Woodward and will present the new British production of Ephemera with Harold Pinter’s poetry before preparing a new translation and film adaptation of the Bacchae.

Current screen work includes the TV production of Lynda La Plante’s Supply and Demand and Fivi Fildissi’s new film, Between the Lines.

He is now based in London.

Mostyn Lawrence: Being an established and successful actor, director and writer in Greece, what inspired you to come to London to work?

Nikos Dionysios: It’s a combination of things. First of all, I was in North America. After this I went to Toronto and New York and stayed there for ten years. I adapted to the life style. Why am I saying this? I am saying this as I believe that London is a crossroads between Europe and North America. So it combines the elements that are necessary for myself, for my lifestyle, which is the European – very classical – the new modern Europe – and then, on the other hand, there’s North America, another kind of mentality. I now believe they are both in me. I feel very comfortable here. London is the centre of Theatre. There’s a sense of connecting with all other artists from around the world. There’s very much a feeling here of people judging your work and I like that, I love this. I love being judged by London audiences.

ML: How is British theatre perceived by the industry in Greece?

ND: It’s very high. There is a very respected attitude towards British Theatre. Most of the people in Greece visit London to get new ideas, to find new plays, new writing. Many people come here to find inspiration. ML: What’s the training process like in Greece?

ML: What’s the training process like in Greece?

ND: Most of the schools start with improvisation, right from day one. Because many theatres own drama schools. There they prepare the students for their own theatres, which is good – they get a kind of direction for a specific kind of theatre.

ML: Similar to the Rep system over here?

<ND: Yes.

ML: You’ve written and directed many pieces in Greece, do you have any plans to produce work in the UK?

ND: Yes. I have been working on a production with Harold Pinter’s Portrait called Ephemera. I am in the process of completing the play and we are looking for producers soon.

ML: What do you think of English Theatre’s interpretation of Greek dramas?

ND: I think they do great work with Greek drama. The only consideration I have is about the cause. The cause is not being held in the right way. Which is understandable as the training here deals mostly with Shakespeare. You deal more with characters. In Greek tragedies, we deal more with symbols and with symbolism. I think the whole effort with Greek tragedy is very good.

ML: Creatively, what is happening with writers in Greece? We don’t have many Greek contemporary pieces transferring to Britain.

ND: This is true. In Greece, at the moment, we don’t have the contemporary type of writers that are in touch with present times. Or there are people that have not had the opportunities to show their work.

ML: It’s very hard for producers to find the vast amounts of money needed to stage productions in this country. Is this a similar problem in Greece?

ND: It is. It is very expensive. They create huge productions. For a new writer today it is very difficult to be trusted. I don’t think it’s good, because, I think Theatre must give opportunities for new people because there is always rebirth for Theatre, and if they don’t do that, ultimately it will die.

ML: Do you feel that’s what’s happening in London at the moment?

ND: I believe “yes”, in a sense. I think it’s better than other countries – London, because there’s such a competitive way with Theatre here. That always helps to give opportunity to new talent. Plus the British mentality, as well, that gives a chance to the young people. But I think, today, it’s less than the seventies or the eighties.

ML: What is your view on fringe theatre?

ND: This is the very good thing with British theatre. An audience loves taking a chance, viewing something that they don’t know. I think that starts because of love for  Theatre. Which is also very important. Fringe gives the opportunity for people to try things. By doing this, they are creating a new type of tradition that’s going to help later in the West End, or the more commercial world of theatre here. I believe there is a kind of mentality that thinks it’s not professional. Sometimes people regard Fringe as “not professional theatre”. I believe this is not good because it creates less demand from the artist. I believe that Fringe is the hope in this city. The West End should expect more from the Fringe and give even more space to the Fringe world, without regarding it as “not professional, as amateur”.

Theatre. Which is also very important. Fringe gives the opportunity for people to try things. By doing this, they are creating a new type of tradition that’s going to help later in the West End, or the more commercial world of theatre here. I believe there is a kind of mentality that thinks it’s not professional. Sometimes people regard Fringe as “not professional theatre”. I believe this is not good because it creates less demand from the artist. I believe that Fringe is the hope in this city. The West End should expect more from the Fringe and give even more space to the Fringe world, without regarding it as “not professional, as amateur”.

ML: What’s your view on productions that are spectacles more than issues?

ND: So, you’re asking me to be a little bit hard?

ML: Perhaps.

ND: Yes. (laughs) I feel that we’re losing the real sense of Theatre. There’s no communication with the audience. The other element is that we have no relationships on stage, for instance. We have actors that speak for themselves, like individuals. And Theatre, for me at least, is a game, a live game of sentiments and relations. I think this is the trigger for the audience, the magic and the mystery of Theatre. I think we are losing that. Also, we are losing the sense of beauty. Today we create beauty on stage with technicalities, with lasers, with huge sets. There is the simple beauty, which is the Theatre itself. I think we are losing that. It’s a disgrace if we do lose it completely. If this happens then Theatre will have no role to play in the Arts. A very simple example is that more and more theatres are adopting the use of microphones.

ML: What’s your view on the Theatre industry here in London?

ND: I think there’s a problem, at the moment, as I don’t see new exciting ideas going further. It’s a transitional period.

ML: You’ve held master classes in theatre training institutes in this country. Do you see a difference in standard and subsistence to the training you received in Athens compared with the training that’s given in this country?

ND: In general, with many countries, today’s drama education is more for television and not for theatre and that creates a problem – that the students and tomorrow’s professionals are trained for television and not for personal contact with the audience and I believe there we have a problem.

ML: Do you believe there’s not a craft being taught any longer?

ND: In a sense yes. To be more justified it is less than before. There is more attention to working in a studio. There seems to be a video between the auditorium and the stage. This problem is not only here, it’s in Greece as well, in North America, in France, everywhere. Instead of having people being inspired to get into theatre, people are using it as a stepping point to get into films.

ML: Do you think this is a reflection of the training that’s given in this country?

ND: Yes. This can be overcome with a good director and enough rehearsals; with a director who really wants to work with the actors – not just being a person who arranges the movement and the relation with the set and the costumes. If a director – like the great Masters – and we have great Masters here in England – who deal with the actor, and they expect from the actor things to happen. I think the actors will adapt, and they will find first of all the strength, and secondly, slowly learn how to project because that will be demanded. They will do it, if they have the talent, the physical talent. And there is the gene of Theatre, that if the director will ask them to project, and be sincere with that, they will do it. I believe the actors are the last to blame – I’m an actor myself - I’m sure if we go on stage, we want to set the sky! First ourselves and secondly the audience. I believe we’d do anything to do that. Now we need the Master who will be mild. Actors are like kids, actors need the imagination. The problem lies with education and the general way we regard Theatre today. There used to be more time for rehearsals in the past. Now it’s less and less. When you’re asked to do something in a matter of three or four weeks, and we have a great writer and a really difficult play, how much really can you do? In general, the situation doesn’t help to create masterpieces.

ML: What’s your view on casting in this country?

ND: Casting directors and producers, they always try to find the commercial element and most of the time they stay with the look and not with the talent. There is a tradition in America that there are many stars. If you go with the look, they shouldn’t be there. (laughs)

ML: Are you working on any projects at the moment?

ND: I have projects at present in Greece, Paris and currently I’m in discussion for productions in London. There are many things happening at the moment.